Stories

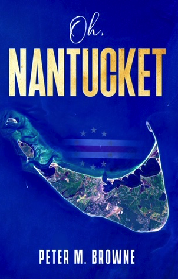

The Cover Story

Readers have inquired about this unique cover. Why is the Cape Verdean flag faded and barely visible. Because, it represents the circumstances surrounding the Cape Verdean people on the island during the period of the story — the short answer.

If a picture is worth 1,000 words this image certainly lives up to the claim.

Cape Verdeans were treated as second class citizens to be hidden away from tourists and vacationers, not allowed to obtain any employment that was customer facing. Assigned to working in the back or off hours when shops, businesses and goverment establishments were closed to the public. They were deprived of equal opportunity and fair treatment.They were in society's shadow.

MoreConfronting History...

The social justice awakening across America has brought attention to the untold histories of people of color, their struggles, their sacrifices, their ability to endure and prevail over oppression, discrimation and demonization.

While Nantucket is no "Black Wall Street", the discrimation against minorities, on island, was the cause of generational suffering, loss of economic opportunities, equity and inclusion. It drove families to despair and other families to depart.

Reparation is not a possibility, for those most impacted have long departed, but acknowledgement of the truth is essential to healing — Truth before reconciliation!

MoreJune 2001

Excerpts from Inquirer & Mirror and Other Islanders...

American Historian Dr. Martha S. Jones reminds us, "People forget that history is not merely a recounting of past events but also a battle over who writes it, from which perspective and what those stories teach (us)..."

Resident Cape Verdeans, James Duarte and Augie Ramos, lamented the fading of their culture on Nantucket. Ramos was quoted as saying "The ethnicity is gone..." He also noted in a subsequent interview that the sense of community has been lost for some 30 years or more.

Others observed that it was not that the younger generation was not interested in their heritage. They were asking "Who are we?" and came to think of themselves as Cape Verdean — not African-American or simply of mixed race but people with a distinct heritage. Today, where there are sufficient numbers, social Cape Verdean communities are thriving with all the circumstance once identifing the physical Cape Verdean communities of Nantucket and elsewhere.

For "historian" Frances Karttunen, in her book, to simply say that Cape Verdeans arrived in Nantucket via whaling ships and now hold prominent positions in the Nantucket community is a "Big Leap", it glosses over the importance of the struggle the Cape Verdean community endured on that journey and its cost in terms of life, quality of life and the equal opportunity for social and economic advancement.

She references these issues briefly in Chapter 5 of her book", though obstensively having done the research, she eliminates the details that humanize the story. She states and I paraphrase, ... economic pressures sent Cape Verdeans to Southern New England. Economic pressure is a euphomism for the death of tens of thousands of Cape Verdeans due to starvation and disease brought upon by centuries of drought.

In fairness to Karttunen, her book provides an execellent chronology of events of "Other Islanders", but is otherwise devoid of any representation of the Cape Verdean language or culture. It does, however, elude to the racial divide between people of Portuguese descent, "Some immigrants from Portugal and the Azores don't like to consider Cape Verdeans... as Portuguese." Additionally, she points out incidences of institutional racism on Nantucket, in the Catholic church, the Steamship Authority, the newspaper and employment. None of these topics are fully examined in her book or any of her work with the Nantucket Historical Association's Cape Verdean exhibits. It appears neither the NHA nor representives of the Cape Verdean community working with the NHA feel these issues to be historically relevant. What happened yesterday matters today. That is the reason my novel, my blog and this website have been created. I present the history of Cape Verdeans on Nantucket and the conditions they endured — warts and all.

Nellie and Joe

There are so many who knew Joe Lopes and spoke highly of him, most from his time as dockmaster for the Nantucket Boat Basin. But, for me it goes much further back. Joe Lopes and my mother were born the same year, 1918, and were close friends for their entire adult lives. Joe married my great Aunt Nellie and became a part of our extended family. He was my Godfather and a key figure in my life growing up. He was there for me on so many occasions. He gave me my first motor scooter, went with me for my driver’s test and he pulled me from the water when I fell in and almost drowned.

Back then, though, it was always Aunt Nellie and Uncle Joe. They were inseparable; the dynamic duo in our family circle. As they used to say, "Behind every great man is a great woman." She was certainly the outspoken demonstrative one. Joe was low-key but self-assured. Aunt Nellie would propose and Uncle Joe would dispose.

I would describe Aunt Nellie as having an air about her. She was not aloof but, in her way, she was above it. It, being the circumstances within which she found herself; a member of a minority on Nantucket, in a less accepting time. But there were two Nellies, the one who worked for white-folks, cooking and cleaning, who was mindful of her “place” but commanded and received the respect of her employers. The second Nellie was my aunt, selfless and caring, confident in herself and her true position in life. She expected that she deserved the best and pursued that dream until it became a reality — fake it ‘til you make it.

Joe made sure she had the best of everything, based upon what they could afford. He even built a boat for her, virtually from scratch, overhauled an old motor and created a poor man’s yacht. On Sundays, when the work week was done, they would get family and friends together and head out into the harbor to emulate the wealthy, cruising and having cocktails. Kids were not allowed on the Sunday excursions, Aunt Nellie’s orders. This was a time for the adults to kickback after a week of hard work. But Uncle Joe would always make time to take the kids out for a spin around the harbor during the week.

Aunt Nellie had been married previously and had two daughters, but you would never know they were not his own. And when Nellie’s granddaughter Franchester was born he became Papa Joe to the next generation of kids.

Story Continues...1897-1981

Anna Gomes — Reluctant Entrepreneur

Anna Gomes was born Anna Viera in Harwich Massachusetts on April 8, 1897. most of her siblings were also born in there except her youngest brother John who was born on Nantucket in 1910. Anna was a most precocious child. When her parents, Peter Viera and his wife Rose, moved to Nantucket is not exactly clear, nor could I find records showing when they took up residence at 17 Washington Street.

Her father was from the Cape Verde island of Fogo, which means fire and is reflective of the volcano that dominates the island. Her mother, Rose, on the other hand, was born in the Azores. He was a person of color and she was white. How they were able to meet, fall in love and marry, in a less than racially tolerant time is unclear.

It appears that neither of her parents was literate, resulting in Anna being required to learn Portuguese in school, in order to write letters allowing them to communicate with family members in the "old countries." Why she was chosen for this task is unknown.

Anna was the middle child. Her siblings; Mary, Joe, Nellie and John all lived on Nantucket for a time. Mary was known to us as Tita Bayi (sp.), Joe as Ti Jeja (sp.) and the younger two as simply Aunt Nellie and Uncle JV. The reasons why the older aunt and uncle were referred to in Kriolu and the younger in English is an unanswered question. As children we just mimicked the way others referred to them.

Anna would meet and marry Manual T. Gomes, at an early age. They in turn would have 7 children; Evelyn, Rose, Marianne (Marion), Mary (Margo), Peter, Manual Jr. and Alfred. It was a hard scrabble life. Work was hard, unpredictable and often scarce. Rose would die at the age of 19 from scarlet fever. The other 3 sisters were forced to leave the island in order to find any form of permanent work. Each would obtain employment, in New Bedford, as a live-in domestic with a caring family. They were treated well but were separated from their family in Nantucket for protracted periods of time.

On Nantucket, two generations of males did their best to remain employed. Uncle Joe was fortunate enough to obtain a job with the town’s highway department and Peter became Harbor Master briefly. Military service took the younger men away for a time.

In the winter of 1956, on a chilly day, Manual T. Gomes would die from a stroke while walking home. Anna would become a widow at 59. She had never really worked outside the home. Her job had been raising the kids and due to circumstances, her grandkids as well. She had taken in laundry as a means to earn some additional funds and had gone along with her sister Nellie on some Spring cleaning jobs, but she was first and foremost a homemaker.

Without a pension, social security or any other means of support her financial future looked bleak. Her children grown, some moved away, some deceased, she was largely on her own. She did have one asset, her home at 53 Washington Street. She could sell it but then where would she go, plus she was still raising her youngest grandchild, whose father had died unexpectedly.

She decided to convert the family home, of over 30 years, into a boarding house. She would rent rooms on a weekly basis to workers needing housing. Having no experience, she would intuit all that was required; advertising, pricing, screening, monitoring and managing renters. Be mindful that this class of renter was young, largely irresponsible and mostly indifferent about rules and protocol. In addition, there was the cleaning, laundry, policing and the weekly rent collection — the renters, not the most reliable or trustworthy. But in true Cape Verdean fashion, sufri kaladu, suffer in silence, Anna rose to the occasion. She managed her properties, which included the shacks in the backyard as well as any hotelier. For the next 25+ some years she would remain solvent and self-sufficient. And when she passed her properties at 53 Washington Street would be free and clear of any encumbrances.

Wall of Remembrance

Within the stories and media presentations are references to people and scenes. The following collection of photos and art work bring those elements together in order to paint a more complete picture of the life and times described.

This wall is a work in progress.

View The Wall